by Isabella Pellerito Lucy

What happens to former U.S. military bases abroad?

Post-Base Urbanism

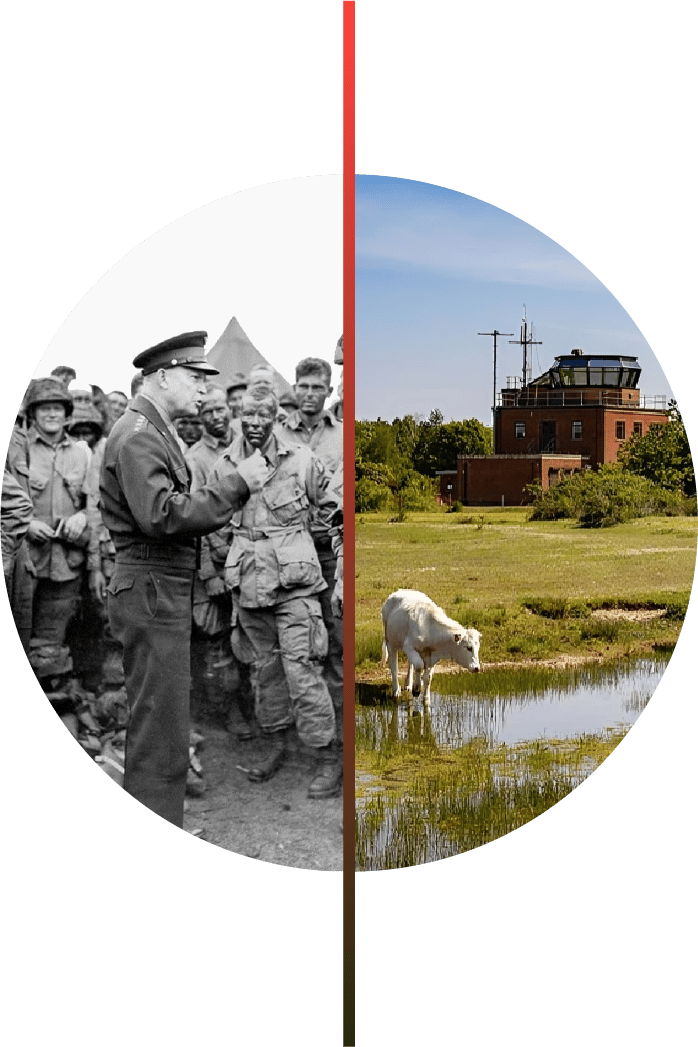

While it's easy to pack up small bases with few traces of use, medium and main operating bases are packed with valuable infrastructure.

Missions to bases in the Middle East are considered “hardship deployments.” In order to cushion tours, the military boasts amenities ranging from fast food outlets—Cinnabon, Burger King, Pizza Hut, and KFC—to indoor swimming pools, movie theaters and spas in addition to infrastructure like post offices, fitness centers, and hospitals. As a kid, I was often stupefied that we could go on base in Italy and things would look very much the same in England or Belgium—even down to the floor layouts at the Commissary.

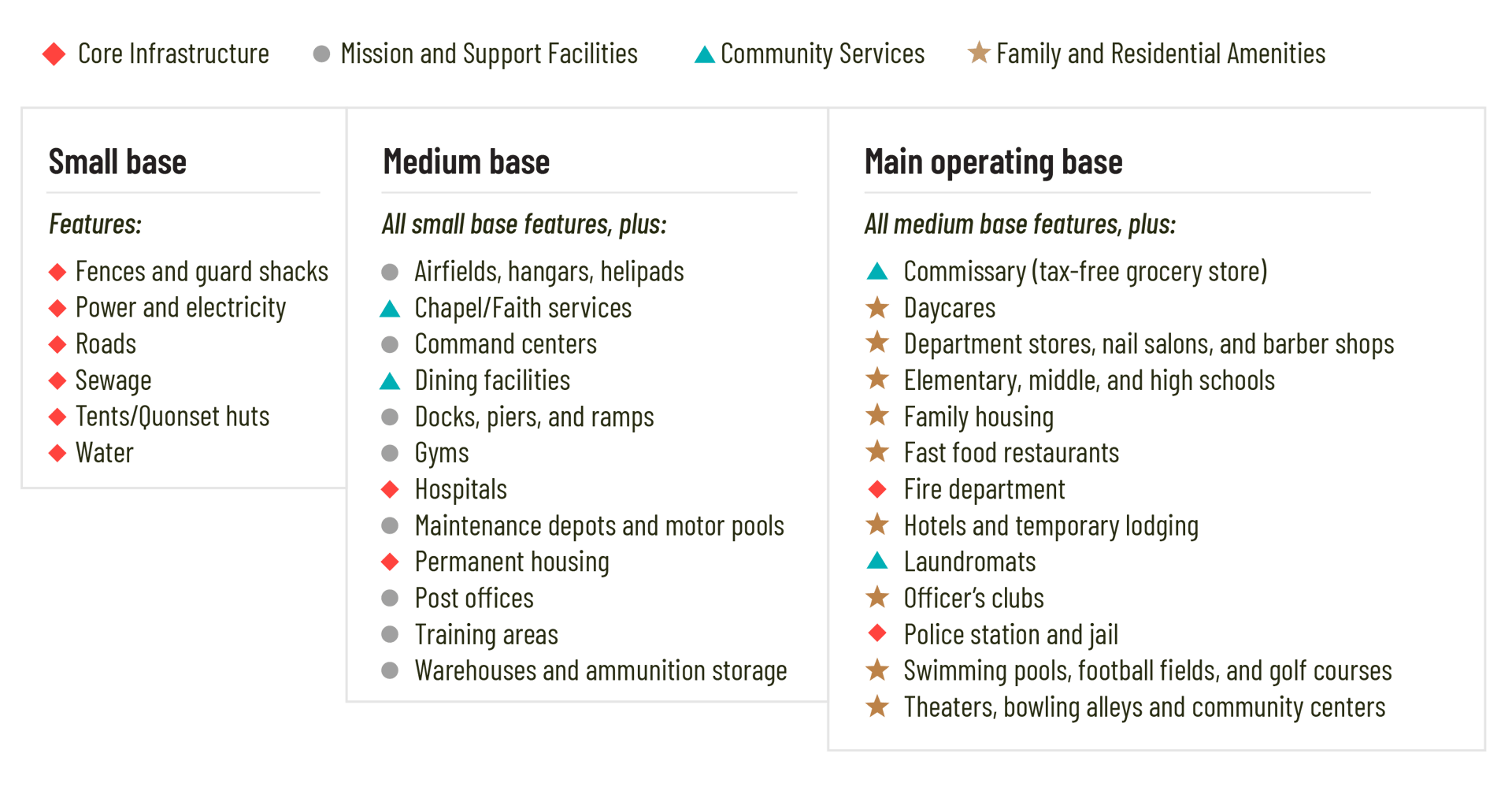

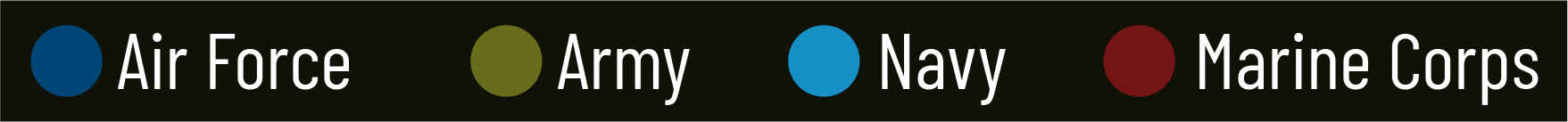

David Vine, author of Base Nation and expert on the U.S. military presence abroad, groups bases into three categories. Small bases, also known as lily pads, often rely on contractors (or a handful of troops), are worth less than $10 million, are smaller than 10 acres, and may not be in constant operation. Medium bases house soldiers and have some amenities, like fitness centers, but no family members. Main operating bases, or little Americas, are worth more than $10 million, are larger than 10 acres, and usually employ 200 or more service members in addition to their families. I’ve also included the expected infrastructure and amenities based on classification.

If the last thing you may expect to see in the desert is a Cinnabon, you’re not alone.

Not all bases are created equal

For our safety, we traveled in a tourist bus to mask the large group of Americans on board, checked in at the guardshack with our military IDs, disembarked, unloaded, and began our sale with a short, two-hour window to minimize risk. Soldiers swarmed our booth, eager for a taste of home and a distraction from the monotony of living and working on a bare-bones base in rural South Korea. We sold every box.

The daughter of Department of Defense educators, I was born in Germany, and grew up in South Korea and Italy. After my brothers and I were born, my mom, an Air Force veteran and former intelligence officer, transitioned into school counseling, and my dad, a historian and former contractor, became an elementary school teacher. The places I grew up in make up three of the most militarily-occupied countries in the world. As civilians living in military communities, my family had access to all the base's amenities: education at Department of Defense Dependents Schools, youth sports through Morale, Welfare & Recreation, food at the Commissary, shopping at the Base Exchange, and more. Later on, I write about how KPOP star G-Dragon now lives where I used to catch the bus and how my middle school was demolished to create an urban park.

If I ask you to picture a military base, chances are a scene from a Marvel movie will pop into your head: some version of a massive, sprawling, high-tech, compound filled with soldiers in formation and American flags everywhere. Today, many military bases have that plus all the comforts of home: single-family dwellings, schools, fitness centers, shopping complexes, places of worship, movie theaters, fast food joints, and more. This is by design. In 1945, the Army permitted families to begin accompanying service members abroad, prompting an explosion of sprawling, city-like bases that exist to this day. Currently, the U.S. military has over 800 bases outside the U.S. and its territories, from single-shack sentry stations to full-fledged Little Americas, replete with Taco Bells, football fields, and massive cars. But what happens when wars end, leases expire, or local pressure brings the troops home?

The first time my Girl Scout troop traveled to sell cookies, we hopped on a bus to a small military base north of Seoul—within scope of North Korea’s short-range missiles.

Note: This table generalizes from publicly available information. Not all bases in each category will have have every amenity, as they are highly dependent upon branch, location, and construction year.

A closed area with its own architectural language.

Description of the Dreipfuhl housing area in Berlin

How are bases initially constructed?

From New York City to Seoul and Chicago to Berlin, American cities look very different from their global counterparts and bases are no exception. Construction of military bases regularly defied local planning and zoning standards, construction methods, and space requirements.

Depending on the type of base and its anticipated use, housing options range from tents, Quonset huts (steel fabricated structures), barracks, apartments, suburban-style bungalows, and pre-existing subsidized housing off-base. Engineers often lived in tents while constructing the rest of the base. Water supply is next up, followed by electric grids. Fences, guardshacks, and checkpoints enclosed these facilities. In some cases, bases don’t even meet this criteria, especially in the Middle East. In Iraq, the former Bashur Air Base was, “the epitome of a bare base. It was nothing more than a 7,000-foot runway in the middle of a green valley. It had no infrastructure—no water or sewage system, no electricity, buildings, or paved roads.”

The U.S. Navy's Construction Battalions grading land for Cubi Point, Philippines, 1953.

Trucks unloading coral for a bomber runway in the Mariana Islands, 1944.

Function, security, and quick deployment are top priority over form, comfort, and longevity. A historical document from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in eastern Asia states, “The first goal, keeping U.S. forces ready to fight, could not be allowed to fail. The second goal, providing comfortable living for U.S. personnel and families, was not as clear-cut.” Despite the cost of maintaining these bases—Vine estimates at least $71.8 billion every year, conservatively—they are often lacking substantial investment. Architects and planners charged with the responsibility of rehabilitating former bases have described them as having, “oppressive uniformity,” “lack of public space with an urban character,” and “little regard for enhancing the quality of life.” In Germany, Augsburg’s city planner believed American development in the area was, “in absolute contrast to Augsburg’s city planning customs and thus caused damage that was not amendable.” Let’s explore the foundations of American base building:

Military housing in Saitama, Japan, 2019

Suburban Modeling

Bases are often built with the suburban ideal in mind: sprawling, low-density, cookie-cutter, and car-dependent. In Berlin, officers lived in bungalows with two car garages, mimicking American suburbs and representing, “a closed area with its own architectural language.” In Reykjavík, the base was a town in itself, with a school system, fast food, and the only baseball fields in the country. In Tokyo and Seoul, single-family homes with lawns, wide streets, and garages stand starkly against high-density, multi-level apartment buildings.

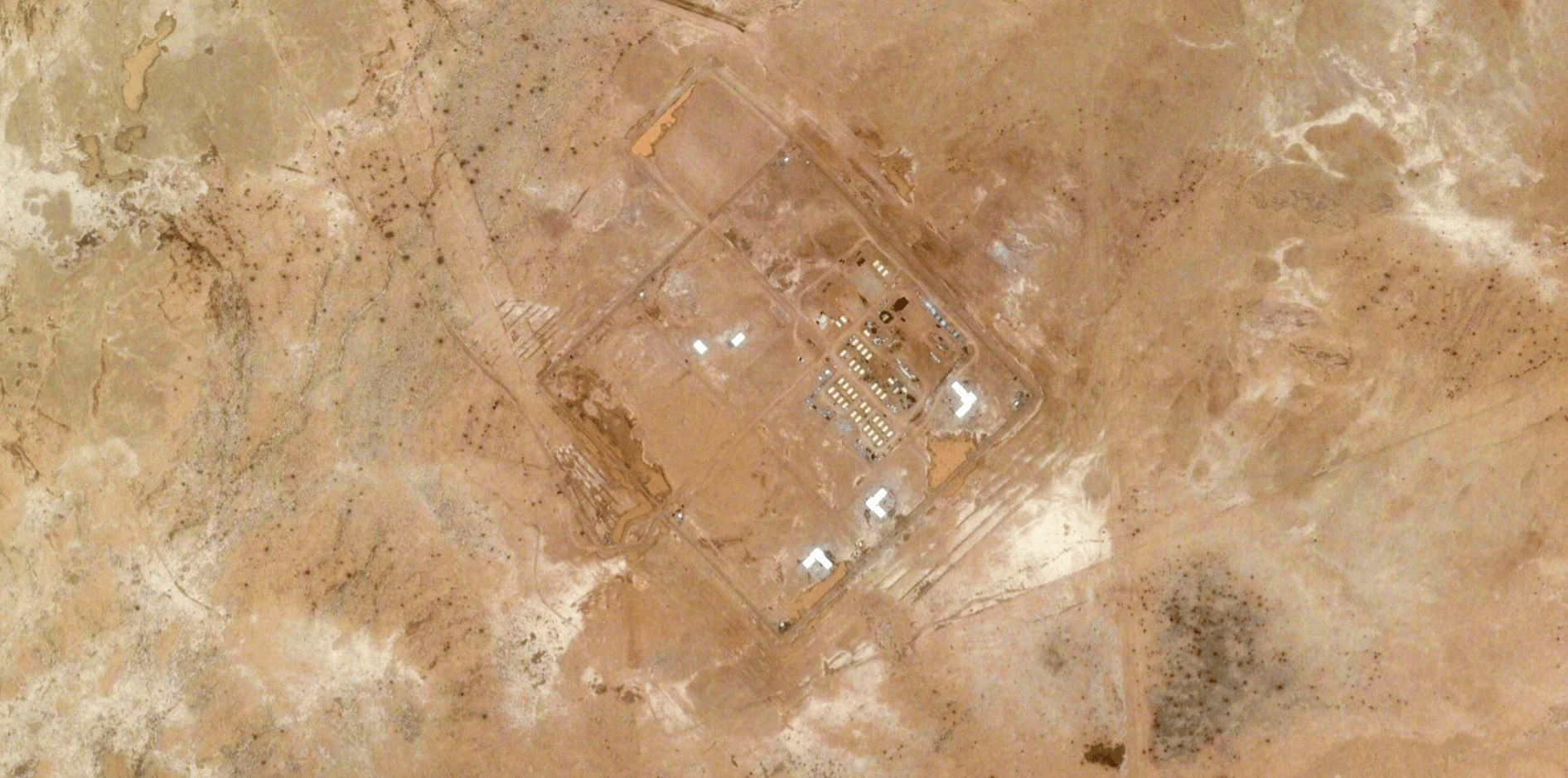

Former Camp Market, South Korea, 2023

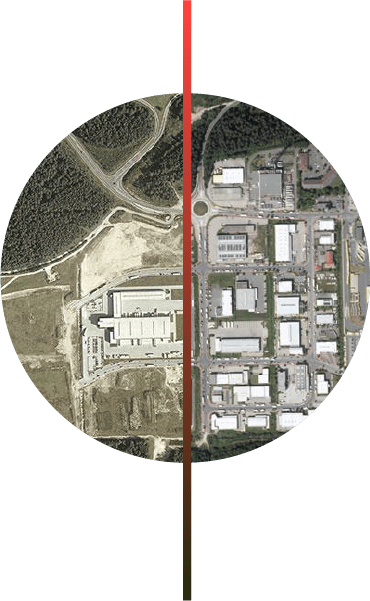

Formerly Remote Locations

Bases are often constructed in remote areas, prioritizing strategic chokeholds or vantage points. However, in cases where urban development has sprung up around the facilities, they become a development barrier for host nations. This is the case in Berlin, Tokyo, and Seoul; and less well-known locations. In the seaside town of La Spezia, Italy, locals believed the base blocked the expansion of the city, forcing development inland.

Chaumont Air Base in France, 1962

Car Dependency

Due to remote locations and access for large, military vehicles, bases are also very car-dependent. In Italy, the base my family lived on was small enough to walk anywhere in 20 minutes, yet huge roads bisected it. Rarely did you see any traffic at all. When we would drive on-base to Ramstein Air Base in Germany, we’d traverse a massive road that also doubled as an emergency landing zone for planes.

Lawn maintenance in Schweinfurt, Germany, 2012

Low Density

Density and scale also play key roles.

The U.S. is on the lower side for population density, ranking 65th in the world with 242 people per kilometer. Meanwhile, countries where the U.S. has built bases—for example, Aruba (600 people per kilometer), the Netherlands (544), and Japan (337)—have much higher densities. Building away from local density breaks the norm. This idea of scale is also pervasive in planning and construction: globally, local communities have protested against the size of American apartments and appliances.

David Vine, author of Base Nation

U.S. taxpayers... pay an average of $10,000 to $40,000 more per year to station a member of the military abroad.

How many overseas U.S. military bases are currently in operation and who pays for them?

Bases range in size from single airstrips to sprawling estates. Some of these places have been closed to the public eye for generations. The oldest U.S. base still in operation, Guantanamo Bay, is a household name. Who is funding all this? U.S. taxpayers. Vine estimated in 2021 that the cost of, “maintaining bases and military personnel overseas reaches at least $71.8 billion every year and could easily be in the range of $100-120 billion. That’s larger than the discretionary budget for every government agency except the Department of Defense itself.” Additionally, U.S. taxpayers, “pay an average of $10,000 to $40,000 more per year to station a member of the military abroad compared to in the United States.” The simple difference of stationing a service member in San Diego, California versus Okinawa Japan has a $10-40,000 cost difference.

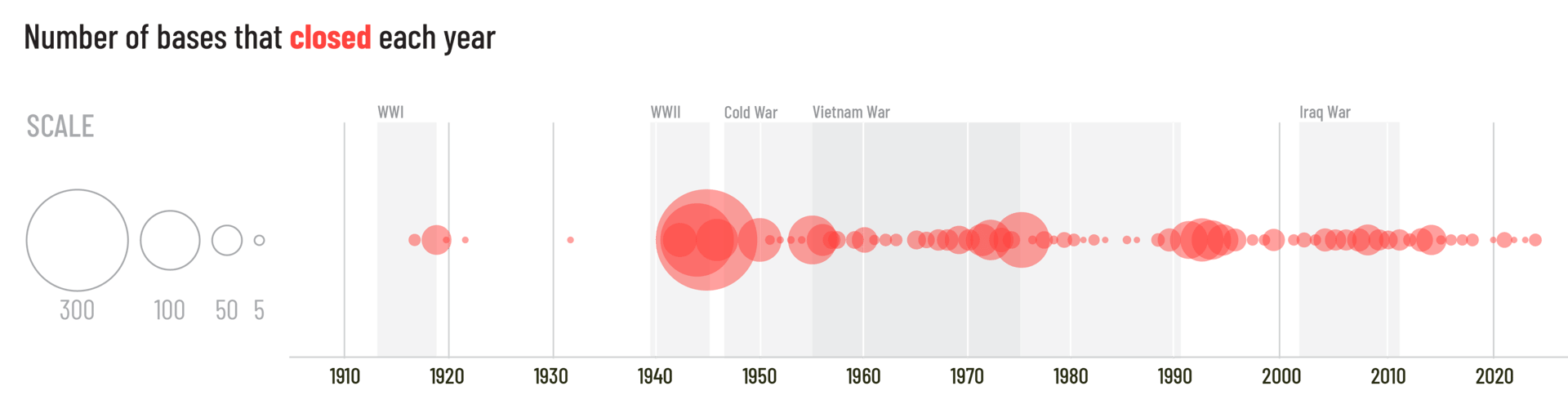

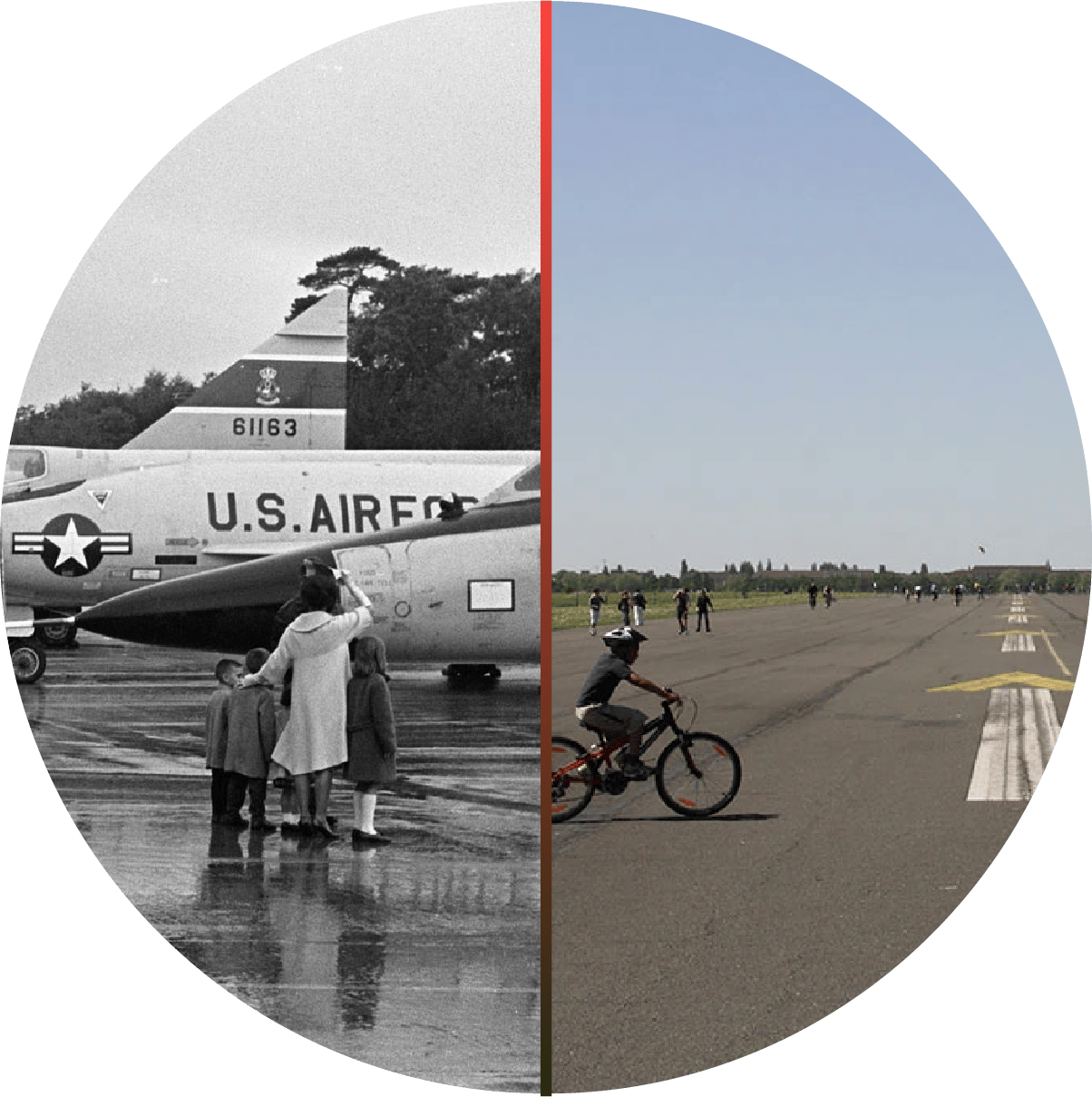

So why do base closures matter? The current administration is putting long-standing institutions on the chopping block—and the military may not be exempt. While over half of bases closed as the direct result of a conflict ending, 42% closed due to budgetary restrictions and strategic downsizing. Since 1898, the U.S. military has closed nearly 1,800 bases in over 100 countries. From Cold War-era radar stations in Iceland to crucial WWII airstrips in Papua New Guinea, base closures affect local populations in different ways. Often, base closures provide unique opportunities for host nations to take large tracts of land, many of which were closed off for decades and create a place that meets the community’s needs. While some closures will lead to once-in-a-lifetime opportunities for development, many take on quieter uses. Perhaps an old training range simply returns to nature or officer’s quarters become homes in tranquil neighborhoods. Regardless, these thousands of sites offer a chance for a second life for the generations to come, especially in places that have been militarized for decades.

Today, there are over 800 American military bases in at least 80 countries around the world, excluding the U.S. and its territories.

The U.S. military has closed nearly 1,800 bases around the world since 1870

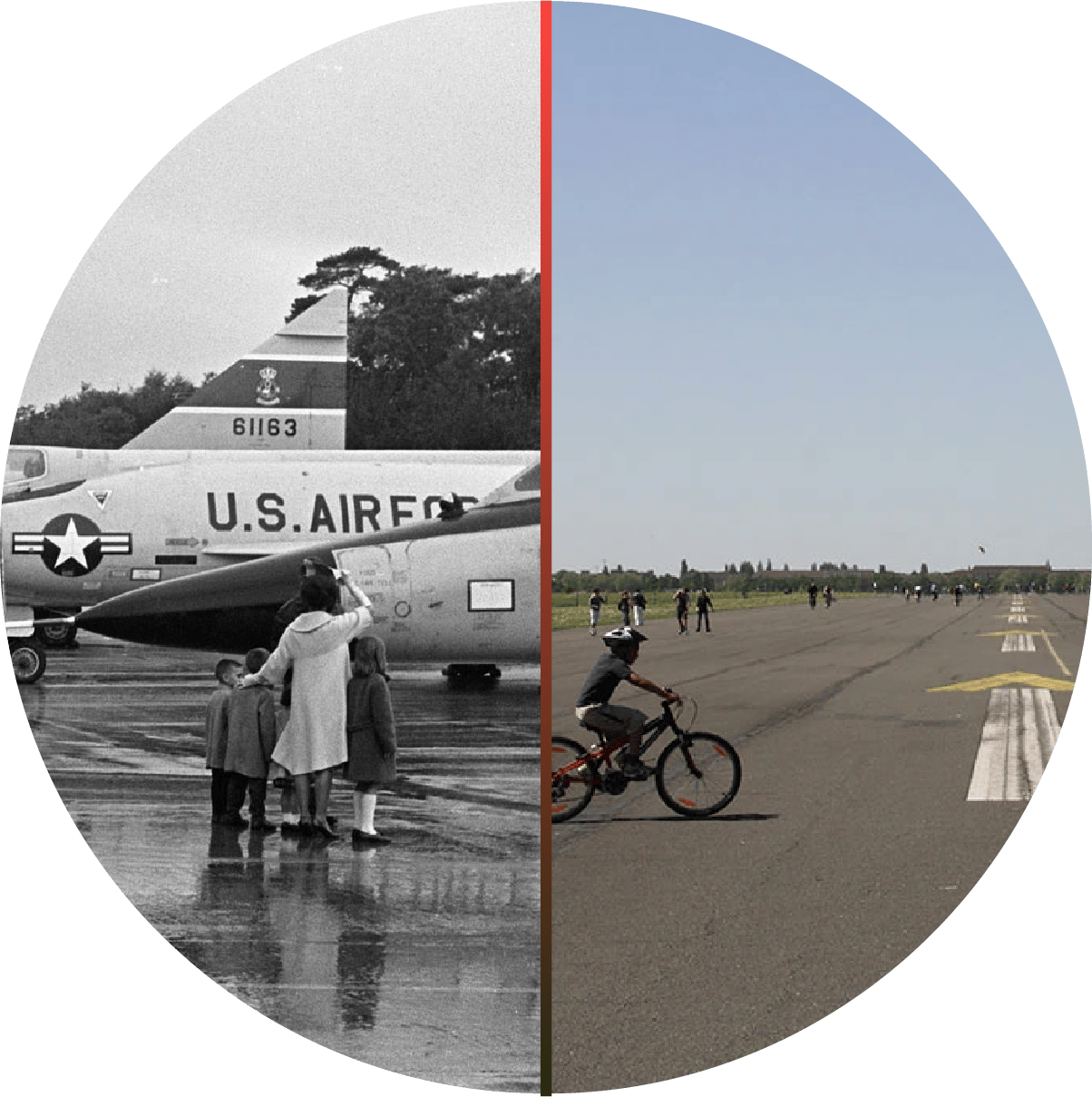

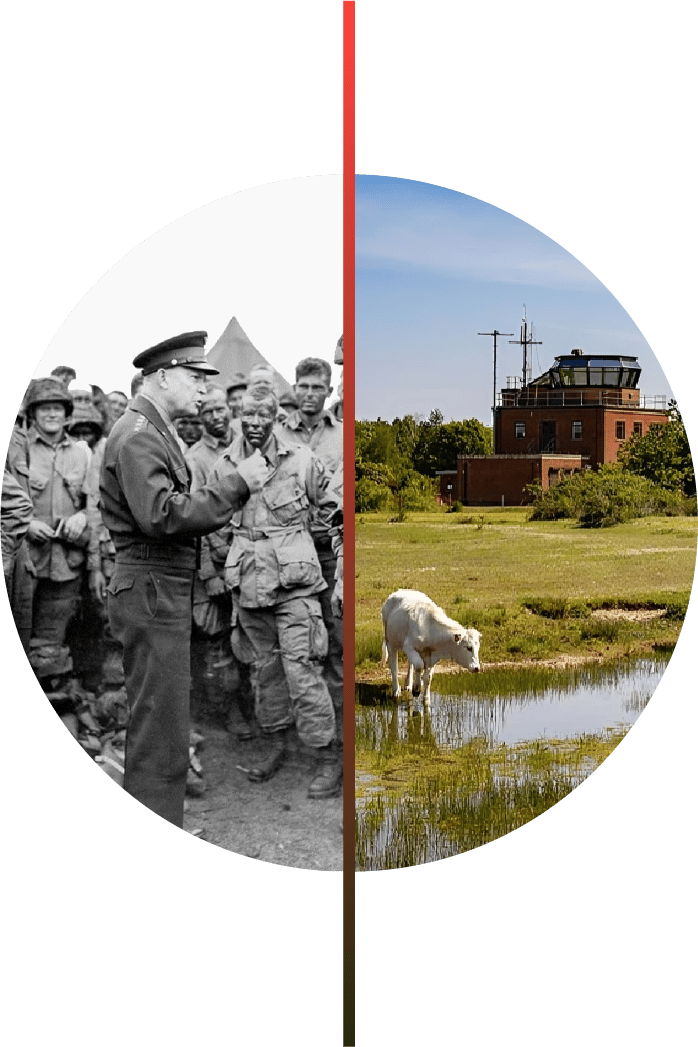

Around the world, government officials, entrepreneurs, sports enthusiasts, and artists have sought creative solutions to local bases closing. Imagine a café nested in a former Air Force control tower, a university campus centered around a helipad, an airport constructed from recycled materials and powered by renewable energy, or rehabilitating Mongolian horses running free on former Army training grounds.

A 2006 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report titled, Turning Bases into Great Places: New Life for Closed Military Facilities, explores this in great detail, detailing how to bridge the community's needs with the base’s existing infrastructure, historical elements, and nature. It posits, “For some towns, the base is already emotionally or physically the heart of the community, and redevelopment simply reinforces that role.” Let's explore some of the most common rehabilitations of former military bases.

The opportunity to transform a former base presents options for local governments, communities, and corporations to stimulate the local economy, address housing shortages, preserve heritage, protect the environment, or bolster their own defense.

Life after the base

17% of former bases are used for aviation. The U.S. military is responsible for constructing several country’s international airports, such as Curaçao, Bora Bora, and Tuvalu. In many countries, an airfield may have been the only real infrastructure harnessed by the U.S., like remote islands in the south Pacific or the arid deserts of the Middle East. Many facilities were seized by enthusiastic drag racers taking advantage of the massive, disused airfields. A WWII airfield in North Bedfordshire became Europe's first permanent drag racing venue.

Aviation: 17%

Turning Bases Into Great Places

Many bases have large, undisturbed natural areas that can continue to provide great habitat for fish and wildlife and recreational space for people.

11.7% of bases revert to their natural state as nature preserves, forests, parks or undeveloped land. Given the U.S. military’s history as one of the largest contributors to climate change, this may seem counterintuitive. However, according to the EPA pamphlet, Turning Bases into Great Places: New Life for Closed Military Facilities, “Many bases have large, undisturbed natural areas that can continue to provide great habitat for fish and wildlife and recreational space for people.” This is especially true for sites that may have only been used for training purposes and no structures were built. Germany alone converted 62 military bases into nature reserves for eagles, woodpeckers, bats, and beetles.

Natural State: 11.7%

Roughly the same percentage of sites continue their military tradition and are handed over to the host nation as a base, academy, military airfield, helipad, or training range.

Military: 11.6%

Over a tenth of former sites are used for farms, fields, and crops. Many of these sites, especially in post-WWII Italy, are former airfields that have been completely reclaimed by nature.

Agriculture: 11.1%

9.3% become residential districts, neighborhoods, villages, or student housing. In cases where new housing was built, units for low-income residents, senior citizens, first-time homebuyers and people with disabilities are targeted.

Residential: 9.3%

4.4% of former sites are currently abandoned. This means base features are clearly visible but have fallen into disrepair or haven’t been put into use by the host nation or private citizens.

Abandoned: 4.4%

Many installations have been given new life, ranging from refugee housing to megastadiums, and war museums to aquariums.

Former U.S. military bases serve over 170 uses today

Click on each circle for more details

Does the military branch play a role in reuse?

Absolutely. In fact, this may shed some light on why the number one reuse of former U.S. military sites involves aviation.

Over half of all U.S. military base closures are Air Force bases

Explore what happened to 1,734 closed U.S. military bases around the world

Today, dozens of former military bases are in the process of becoming business centers, parks, farms, industrial zones, residences, museums, memorial grounds, and beyond. Let’s explore some of the most notable ones.

Hover over each base for more details

Obstacles to reuse

The average opening date of today's military bases is 1946. Rising cost of materials, spatial goals, construction methods, and energy standards are just a few of the things modern day planners and engineers encounter when rehabilitating old bases. Then there are the little things, like outlets lacking compatibility with the host nation, or appliances being too large to fit into locals’ homes.

When bases close in the United States, engineers and contractors are charged with cleaning up these formerly used defense sites. Their protocol is as follows: clean up hazardous substances and contaminants, identify and remove any unexploded ordinances or munitions, and demolish unsafe buildings or structures. Hazardous materials in a military environment could be engine fuel, kerosene, chemical weapons, asbestos, mold, lead-based paints, or nuclear waste. Technology allows them to take stock of old bases’ constructive qualities—concrete, metal, and so on—based on age and location to determine whether there are hazardous materials present. This is especially valuable today, as bases that have been expanded over generations contain more unknowns.

What you just read is the recommended protocol in the United States. A key difference with bases abroad is that host nations don’t have the opportunity to conduct in-depth environmental monitoring and analysis before the land is given back. Environmental cleanup, ammunition removal, and site monitoring are expensive, and depending on the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA)—the legally binding document the U.S. and the host nation cosign—the military may not be liable for shouldering those costs. Vine’s research shows that by WWII’s end, “the military was building base facilities at an average rate of 112 a month.” Bases built quickly may not have taken environmental factors or hazards into account, and those effects would only compound over the years. In some cases, bases can’t always be remediated, or the investment may not be worth it, which may explain why 11.7% of bases have been left to nature, 4.4% were abandoned, and 0.8% were simply demolished.

Architecture firm responsible for rehabilitating Nellingen Kaserne in Germany

These spaces... tend to pose more of an inherited problem than a welcomed asset.

David Vine, author of Base Nation

The speed with which local communities converted former bases into other uses such as hospitals and tourist attractions may have helped to offset any negative [economic] effects.

Base closure sign in Bad Kreuzbach, Germany

Now, he is optimistically overseeing five major construction projects on former bases designed to bring jobs, housing, business, and entertainment to the city.

Military bases are often huge boons for local economies, employing a quota of locals and bringing in hundreds if not thousands of Americans who want to eat, drink, shop, and explore. Stories of bases in rural areas closing and taking the town with them are not uncommon. In seaside Holy Loch, Scotland, a Naval base served as “the area’s main economic engine” and its shutdown was devastating to the local economy. This playbook, with communities often bracing themselves for “catastrophic damage” to their economies, is common. However, Vine explains, “generally the impact is relatively limited and in some cases actually positive. In the case where communities do suffer intense economic harm, most tend to rebound within a few years’ time”

Additionally, as bases grow and expand they become self-reliant, shutting out local communities and prohibiting any chance for economic development or physical expansion. Author Mark Gillem explains, “They are making these bases even more self-contained in an attempt to minimize the need for soldiers to go off-base.” This creates an economic dependence on the base.

Vine’s research states that “the speed with which local communities converted former bases into other uses such as hospitals and tourist attractions may have helped to offset any negative effects.” With preparation, planning, and community backing, communities can transform bases into economic powerhouses, cultural cornerstones, environmental bastions, and highly sought after neighborhoods. Turning Bases into Great Places provides a comprehensive framework:

- Plan for redevelopment early

- Prioritize long-term benefits over short-term gains

- Include the local community

- Explore a wide variety of uses

- Assess the base’s location, existing infrastructure, historical assets, and natural environment

- Design places that “people would be proud to call home.”

When the mayor of Heidelberg first heard of plans to close facilities in his city, he flew to Washington, D.C. in an attempt to sway the military into staying.

A long-standing base is going to close. Now what?

Many of their best practices mirror those already mentioned, like increasing walkability, preserving history, and emphasizing public spaces, with the goal of replacing the jobs lost when the base closed. The report also underscores the importance of creating places with amenities, business opportunities, and character.

An architecture firm responsible for rehabilitating Nellingen Kaserne in Germany wrote, “These spaces… tend to pose more of an inherited problem than a welcomed asset.” But what about the hundreds of success stories of rehabilitated bases? Across thousands of case studies, briefs, and project retrospectives, I encountered many of the same wishes and goals when bringing these spaces into the 21st century: an emphasis on green space, energy efficiency, car-free or pedestrian-focused streets, prioritizing public spaces, and preservation of historical details. At the end of the day, it's up to the government, local community, and associated agencies to assess the former base's offerings in terms of infrastructure, historical ties, cultural remnants and what they want to bring into the future.

In some cases, the past is the best predictor of the future. See what a closing U.S. military base in your region is most likely to become.

Select branch, region, and construction era to see your prediction

Today, former U.S. military bases across the world have been repurposed in almost every way imaginable by host nations. From Japan to Niger and the Bahamas to Kiribati, creative adoptions of existing infrastructure help local communities utilize previously forbidden tracts of land. With such large organizational changes happening in the United States today, it’s paramount that international civic leaders, urban designers, and community organizers take stock of any bases near them and brainstorm possibilities for a base’s next life.

READ CASE STUDIES

EXPLORE BASES NEAR YOU

PREDICTED REUSE TOOL

Download Methodology and Sources

View more of Isabella's work

#1: Aviation

#2: Natural State

17% of former bases are used for aviation. The U.S. military is responsible for constructing several country’s international airports, such as Curaçao, Bora Bora, and Tuvalu. In many countries, an airfield may have been the only real infrastructure harnessed by the U.S., like remote islands in the south Pacific or the arid deserts of the Middle East.

Many facilities were seized by enthusiastic drag racers taking advantage of the massive, disused airfields. A WWII airfield in North Bedfordshire became Europe's first permanent drag racing venue.

11.7% of bases revert to their natural state as nature preserves, forests, parks or undeveloped land. Given the U.S. military’s history as one of the largest contributors to climate change, this may seem counterintuitive. However, according to Turning Bases into Great Places, “Many bases have large, undisturbed natural areas that can continue to provide great habitat for fish and wildlife and recreational space for people.” This is especially true for sites that may have only been used for training purposes and no structures were built. Germany alone converted 62 military bases into nature reserves for eagles, woodpeckers, bats, and beetles.

#3: Military

Roughly the same percentage of sites continue their military tradition and are handed over to the host nation as bases, military academies, military airfields, helipads, or training ranges.

Many bases have large, undisturbed natural areas that can continue to provide great habitat for fish and wildlife

and recreational space for people.

Turning Bases into Great Places:

New Life for Closed Military Facilities

#5: Residential

#4: Agriculture

11.1% are used for farms, fields, and crops. Many of these sites, especially in post-WWII Italy, are former airfields that have been completely reclaimed by nature.

9.3% become residential districts, neighborhoods, villages, or student housing.

In cases where new housing was built, units for low-income residents, senior citizens, first-time homebuyers and people with disabilities are targeted.

#6: Abandoned

4.4% of former sites are currently abandoned. This means base features are clearly visible but have fallen into disrepair or haven’t been put into use by the host nation or private citizens.

Explore current use by country!

Explore current use by country!

Part of a former Air Force base in rural England is now a nature preserve

Here are the top uses of bases globally.